On June 23, 1945, when Gen. Ushijima Mitsuru and Lt. Gen. Cho Isamu committed suicide at the entrance to a cave on Mabuni Hill (known to the Americans as “Hill 89”), coordinated fighting in the Battle of Okinawa came to an end. These deaths, combined with the status of the Battle of Okinawa as the last land battle of WWII, have rendered the Mabuni Hill area a sacred space in the commemoration of the Asia Pacific War. It has also, over time, become the premier site in Okinawa Prefecture’s attempt to position itself as a center of a global peace movement.

From the erection of a memorial to Gens. Ushijima and Cho in the early 1950s (called the “Pillar of Dawn”), through the construction of prefectural and institutional graves along the hill ridge through the 1960s and 70s to the construction of Cornerstone of Peace monument in 1995, the Mabuni area has been the final destination for those from Japan, the U.S. and Okinawa who tour the island in commemoration of those who died in the battle of 1945. The area has contained the competing and often uncomfortably antagonistic memorials of many different constituencies. It offers an excellent site for investigating how many different memories can be manifested in a single space. Yet because Okinawa is distant and travel there is expensive, relatively few Americans have access to the commemorative materials available there.

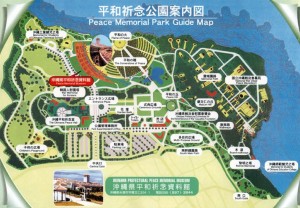

The final installation into this area, the Cornerstone of Peace, is a unique memorial complex, dedicated in 1995, that commemorates the sacrifices of all who participated in the Battle of Okinawa, regardless of which side they were on. It is situated on the basin beneath Mabuni Hill where the commanders of the Japanese forces had their final headquarters and where, therefore, the last stage of organized battle took place. The central component of the memorial complex is an expansive installation of concentrically placed, zig-zagging black granite walls engraved with the names of all Japanese, American, British, Korean and Taiwanese soldiers who died as well as the names of all Okinawans, civilian and military, who died throughout the Pacific War. Modeled after the Vietnam War memorial in Washington, D.C., the memorial materially represents the enormous cost of life of the battle while also methodically inscribing the name of each individual who died in order make the site a place of personal mourning. The walls are themselves situated in a broader landscape that contains a number of individual monuments that been erected since the 1950s, a large memorial park containing graves to the soldiers from Japan organized by prefecture of birth and branch of government service (the closest corollary in Japan to the Arlington National Cemetary in the United States), a gigantic memorial arch, a non-denominational prayer hall and a modern, high-tech museum and conference complex.

The Center is developing a large-scale visualization project that will allow visitors to explore the entire area in close detail, with access to a wealth of multimedia artifacts. The project will feature interdisciplinary collaborations between researchers in the human sciences and engineering and close cooperation with Okinawan and American institutions. The goal of the project is to virtually reproduce a multi-temporal vision of the Cornerstone of Peace on a display array at the UC Santa Cruz School of Engineering known as the “OptiPuter.” The “OptiPuter” incorporates a computational cluster with distributed computing and visualization tiled-display wall. The display wall consists of 40 displays, each with 29.7” viewable area. The displays are laid out in a 5′ high by 8′ wide wall. This leads to a total display size of 202.4” by 79”. These individual displays are capable of outputting a 2560 by 1600 pixel resolution. Collectively, the total output resolution is 163.8 Megapixels. This resolution is high enough to display 80 simultaneous 1080p hi-definition movies.

When the project is completed, users will be able to begin from a contemporary bird’s eye view of the southern half of Okinawa island to recognize the geographic siting of the memorial complex. After zooming in on the entire Mabuni Hill memorial complex, they will have the option of viewing the landscape as it appeared at several moments since 1940. They may start with the present, or peel back a layer to see the hill and basin prior to the construction of the Cornerstone of Peace, or peel back another layer to see the area as the first memorials were being constructed, or peel back another layer to see the area in the immediate wake of the battle or, finally, peel back another layer to see the area prior to the battle. This temporal layering will enable researchers and students to visualize the relationship between historical events and space while also tracing the event’s legacy as we watch a further transformation of the landscape through post-trauma commemoration. To varying degrees, each temporal snapshot of the terrain will be available to explore in close-up by zooming in on particular portions or features. The visualization of the terrain will also be integrated with CSPWM’s multi-lingual database so that the terrains may be seeded with artifacts—photos, documents, audio and video clips and virtual relics—that viewers may investigate in geo-sited context. Further research done outside the setting of the OptiPuter on any feature of the Cornerstone or its artifacts can be added through the database to continually update and expand the Cornerstone exploratorium.

But the Cornerstone OptiPuter project goes even further than a mere representation of a site. Our plan is to build a corresponding display in the museum and conference center complex at the Cornerstone of Peace and link the Okinawan and Santa Cruz displays so that visitors to both may virtually explore the space together, sharing stories and observations and generating ongoing dialogue. We can further integrate the OptiPuter and CSPWM database with Warren Sack’s “Street Stories” cellphone software project to enable visitors to the complex to contribute to the OptiPuter while walking the entire space by simply speaking their impressions and stories into their “Street Stories” enabled cell phones.

Building something this rich and complex requires strong collaborations between many researchers and institutions. Most obviously we need access to a large image archive. Fortunately, these image archives do exist. The Department of Defense has recently declassified a collection of aerial reconnaissance photos of Okinawa that will allow us to recreate the landscape of the area prior to the battle. Use of surviving photographs from Japanese and Okinawan archives will allow us to develop a number of close-up hotspots. The DOD also has extensive images, still and motion, of the postwar Okinawan landscape. The Okinawa Prefectural Archive, opened in 2005, houses an extensive collection of these photographs, the accumulation of visual images of Okinawas modern history being one of its primary missions. Since a significant proportion of Japanese Americans are of Okinawan descent, we will also seek out working relationships with a number of Japanese American organizations including the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, the Japanese American Citizens’ League, the Okinawa Kenjinkai of Hawai’i and the Denshô Project in Seattle. Working with Microsoft’s Live Lab app Photosynth, we will be able to create 3D mosaics of spaces by stitching together multiple photographs of particular landscapes. Finally, a collaboration with Pixar and the Game Design major in Engineering will help us develop simulations and animations that could be integrated into the hyperwall presentation.

The Cornerstone of Peace hyperwall project will generate research and work opportunities for faculty and graduate students in several divisions during its construction. After it is completed it can be used in conjunction with classes in History, Computer Sciences and Computer Engineering, Language Studies and potentially many others. This is because it will be not only a continuously evolving visual archive, but also a tool for trans-Pacific teleconferencing.

If you are interested in further information, or are interested in contributing to or participating in the project, please feel free to contact CSPWM.

Pingback: Gesture of Respect Helps Bury Historical Enmity: the case of the Okinawa flag | History's Shadow