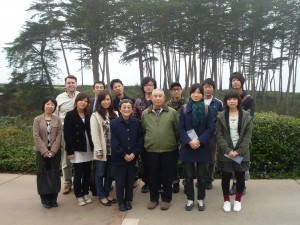

Akira and Hideko Nagamine (front center) with students and professors from Yokohama National University

During the week of February 16 to 19, two professors and nine students from Yokohama National University visited UC Santa Cruz and the Center for the Study of Pacific War Memory. Profs. Matsubara Hiroyuki and Kato Chikako led the four-day visit which included a presentation by Alan Christy and Alice Yang on the projects of the Center, presentations by the visiting students in an American Studies class taught by Emily Moberg and extended interview sessions with Akira and Hideko Nagamine and Mas and Marcia Hashimoto of the Watsonville Japanese American Citizens’ League (JACL).

We hope that Profs. Matsubara and Kato will share with us their students’ reports on their visit. But whether or not the students feel comfortable sharing those reports, we found it very useful to see the kinds of questions Japanese students had for our Japanese American friends.

I would like to highlight two messages, among many, that I thought the Nagamines and the Hashimotos wanted to deliver to the students, messages that they felt came directly from their life experiences.

One of the more interesting, yet simple, questions that a student posed to Mr. Nagamine was a follow-up to his story of living for two years in a village in Northeast China in 1946-47. The village was composed of one-third Chinese, one-third Koreans and one-third White Russians. Mr. Nagamine and his fellow former-Japanese-soldier-sort-of-fugitive settled on the edge of the village for two years and opened some land to cultivate for their own. They borrowed rice seeds from the Koreans, food to eat (while they waited for harvest season for their own rice) from the Chinese and performed manual labor for the White Russians. When they harvested their own rice, they paid back the Koreans and Chinese for the loans of seed and food and had some left over for themselves. For Mr. Nagamine, this experience revealed the importance of getting past people’s ethnic identities and simply forging direct relationships. But when one student asked what language he spoke with the Russians, Mr. Nagamine shrugged, “Chinese, of course.” This question and response planted a seed in his mind and as he was saying goodbye to the students he delivered the following take-home-message: “You should all learn three or four languages. That is the way to get by in the world.”

I could feel the students shrink at his answer. Earlier, during our presentation of the Eternal Flames web project to the students, one student commented that the language gap was likely to be the biggest obstacle to developing Japanese and American student collaborations. He did not make this comment from a sense that American students lacked sufficient Japanese language skills, but from a lack of confidence in his own English language skills. Yet here was this elderly farmer, with no more than an eighth grade education, telling him that he spoke Japanese, Chinese, English and Spanish and encouraging him to do the same. I think the students despaired at the thought of the effort it would take to learn all of those. But as I told the students later, it is important to understand that Mr. Nagamine’s idea of language proficiency is not at all the same as the notion of language proficiency that they have encountered in formal language schooling and language gateway tests. Those settings emphasize propriety and adherence to norms. Mr. Nagamine’s standard is effectiveness of communication, regardless of its evaluation by language teachers. This is precisely the approach to translingual collaborative research that we hope to promote with Eternal Flames.

Mas and Marcia Hashimoto (front center) with students and professors from Yokohama National University

The Hashimotos talked about their experiences in the internment camps (Marcia was born after the war, so she spoke of her family’s experiences) and what those experiences have meant to them today. Marcia is currently the president of the Watsonville chapter of the JACL and Mas has been past president a couple of times. Marcia worked for many years as a kindergarten teacher, while Mas was a history teacher at Watsonville High School. Among the many lessons they took from the camps was the importance of solidarity with other groups facing discrimination and oppression. Although their organization is called the Japanese American Citizens League, they explained to the students that one of the things they provide is a kind of rapid-response to schools and other institutions that are experiencing disturbances relating to ethnic tensions or homophobia. They contact schools that have had incidents and offer to come in and provide counseling and provide a historical understanding of the problems the school is facing. This message resonated well with Mr. Nagamine’s stories of transcending ethnic and national divisions.

Mr. Nagamine still holds Japanese citizenship although he hasn’t lived in Japan for over 50 years. Mas and Marcia Hashimoto are very proud to be American citizens and also proud of their Japanese heritage. For the student who asked Mr. Nagamine how he could contemplate living in the country of his former enemy*, I suspect these meetings provided a lot of food for thought about living in a global age.

*For the record, I don’t think the student sees Americans as the enemy. I think his question was intended to elicit thoughts on reconciliation from someone who had gone from taking arms in war to living peacefully, a transition that, I’m sure, he recognizes as very difficult.